The need for gemological knowledge has been recognized since the dawn of our industry. As is the case today, old-time dealers required technical information in order to make informed business decisions when purchasing goods. Understanding imitations was the main concern and, over time, the concerns evolved to more sophisticated mat- ters such as synthetics and then treatment disclosure, origin, and traceability. Gemological knowledge is now more com- plex and scientific, although classic gemology still remains accessible for the non-scientist.

The communication of all that knowledge evolved with the digital age, whether through written content in online books, articles, blog posts, videos, and social media, or in education, both in-class and at a distance through e-learning plat- forms and other digital tools. A true digital transformation had already begun in gem education, but now, with Covid-19, it became even more evident.

Apart from the master-to-apprentice dynamics, the pass- ing of knowledge in Antiquity was only in reach of the literate upper classes. Old written accounts on gems are scarce and names such as Teophrastus, Pliny the Elder, Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, and Ahmad al-Tifashi are well-known examples. They add to ancient Sanskrit manuscripts, such as the Garuda Purana and a number of medieval European authors, among them Marbode of Rennes. These enlightened souls all documented the characteristics of gem materials, their nomenclature, and occurrences.

Old accounts and methods on how to change the color and/or transparency of gems were known, as in the Treatises on Goldsmithing and Sculpture by Benvenuto Cellini (1500- 1571), with a clear mention of gem treatments. Written documents were, and still are, the basic learning resources.

For many centuries, known gem varieties and their sources were limited when compared to the present. The main concerns of our ancestors were separating gemstones from their imitations or lookalikes. In most cases, jewelers and gem dealers had enough tools to not only classify the materials by their own old trade names, but also to resolve rather simple identification challenges. The secrecy of that knowledge was invariably only passed on from master to apprentice—even sometimes within the same family. Other than the empirical hands-on experience of the masters, books were the repositories for knowledge for those who could read.

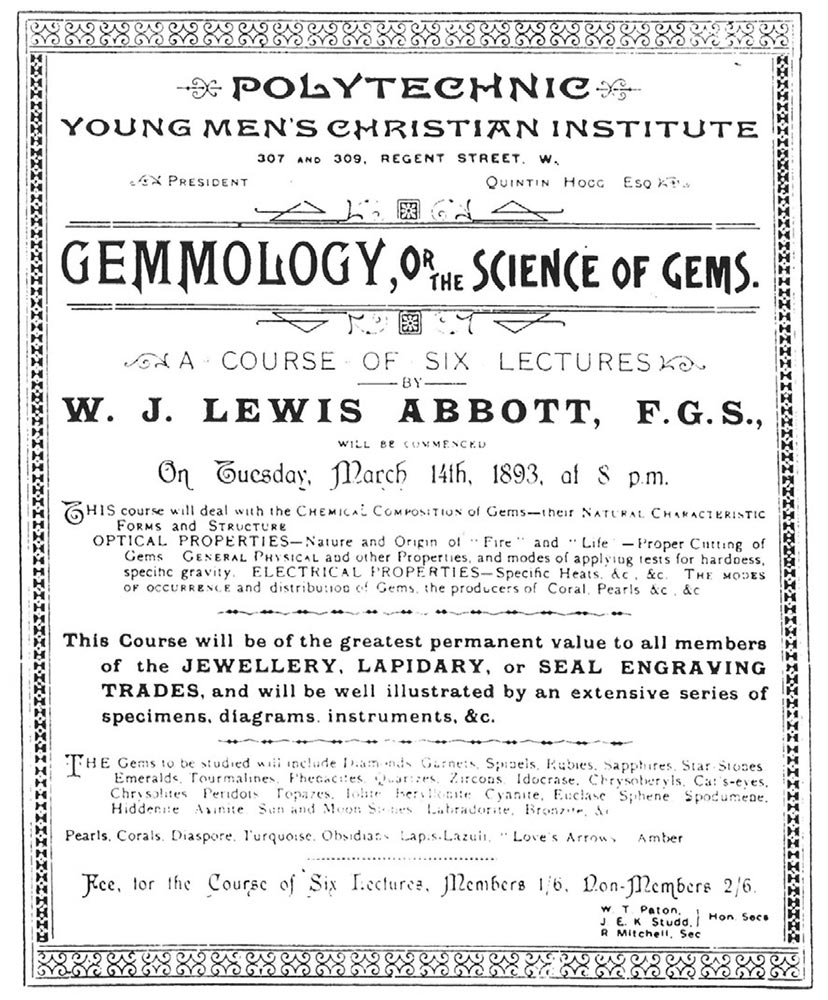

This all changed in the 19th century with the emergence of a middle class of consumers and the early days of massive production. The new social and marketing paradigms would progressively impact the jewelry industry towards the beginning of the 20th century. During that period, scientists experi-mented in producing artificial crystals, as reported in the mid- 1800s, and mineralogical sciences were booming with new methods developed to systematically classify minerals and to document their properties. This resulted in the first gemological events in the 1890s, when British mineralogists conduct- ed workshops in Gemology, or the Science of Gems. Despite the experimental projects with synthetic emeralds and rubies in the 1800s, it was only in 1902 that gem-quality flame- fusion synthetic rubies became commercially available due to August Verneuil in France. Although most production would be used in the watch industry, the man-made stones eventually reached jewelry when unethical dealers misrepresented the cut stones as natural rubies. For the first time and on a global scale, consumer confidence was at stake.

To face these new challenges in the trade, the National Association of Goldsmiths (NAG) in the United Kingdom established an Education Committee and developed the first gemology education courses in 1908. This decision triggered this 112-year gem education journey. Traders and scientists attended the courses, with a special interest in dealing with the increasing number of flame-fusion synthetics, notably ruby, sapphire, and later spinel.

In the mid-1910s, Akoya cultured pearls were introduced by Mikimoto. They had a greater impact in the 1920s, both in pearl-producing areas, such as Bahrain, and in trading hubs such as Paris, Bombay, and London. The need to properly identify cultured pearls was behind the creation of the first gem laboratories in Europe, namely in London (1925) and Paris (1929). With consumer confidence at stake, the trade’s response had to go beyond information offered by labs; education was now a priority.

These concerns prompted the establishment of a department within NAG in 1931, which was called the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. Now known as Gem-A, it became an independent organization in 1937. Many trade associations saw the Fellow of the Gemmological Association (FGA) qualification as highly relevant for the industry, and the next few decades saw an expansion of gemological education throughout the world, either preparing students for the FGA examination or for future independent gemological qualifications. Gem-A’s FGA qualification is currently taught in seven different languages in more than 40 locations in 26 countries around the world.

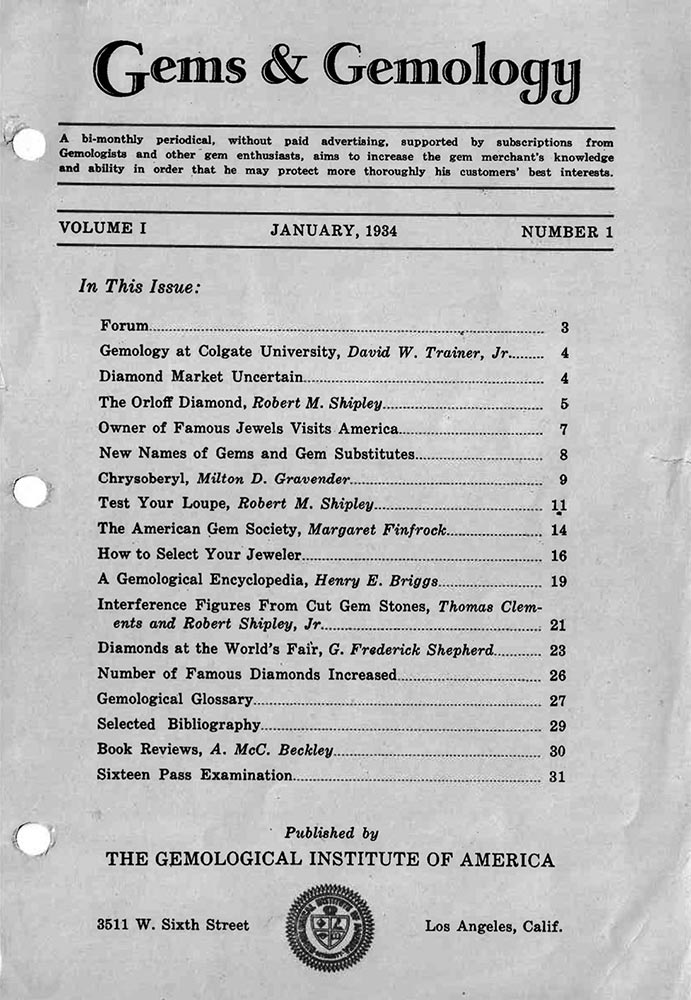

Robert M. Shipley (1887-1978), founder of the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), was one of the early students who completed the NAG gemology correspondence course in the late-1920s. Two years after touring the U.S., teaching gemology to trade professionals, he founded GIA in 1931, offering home-study education in the U.S. Recognizing that knowledge was power, Shipley established the American Gem Society (AGS) in 1934 for knowledgeable jewelers and started GIA’s Gems & Gemology magazine, the first periodical known for cutting-edge gem knowledge and education.

By 1947, GIA issued its first Graduate Gemologist (GG) qualifications and was joined by De Beers in promoting diamond knowledge across America., teaching the “four rules of diamond classification” that evolved into the International Diamond Grading System introduced by Richard T. Liddicoat in 1953. Diamond grading courses started soon after.

The GG qualification is taught today in GIA campuses in five countries and reaches distance education students all over the world. In the following decades, gem education evolved considerably, not only in the U.S. and Europe (particularly in the UK and France), but also in Asia where the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences (AIGS)—the first major international school in Southeast Asia—was founded in 1978 in Bangkok, Thailand.

Aside from Gem-A with 35 international partners (allied tutorial centers) and the GIA with seven campuses—offering their FGA and GG qualifications, respectively— many educational organizations are now teaching formal gemology across the globe. A few have transformed into supranational organizations such as the FEEG, the Federation for European Education in Gemmology, which has promoted the European Gemmologist (EG) qualification since 1995 at 12 teaching centers in eight European countries.

University level qualifications in gemology also exist in some countries. Among them is the Birmingham City University, which recently launched an undergraduate three-year gemology program BSc (Hons) in its School of Jewellery. In the U.S., both the University of Arizona and Arizona State University have announced gemology programs. The University of Barcelona has offered gemology programs for years.

It is interesting to note that jewelry-related schools offer gemological training associated with their regular crafts education, e.g. L’École, School of Jewellery Arts, supported by Van Cleef & Arpels, in various parts of the world, and the Laboratoire Français de Gemmologie (LFG), in cooperation with the known Haute École de Joaillerie in Paris. Distance gemological education has always been offered, first as correspondence courses, such as the one Robert Shipley took in London, and today mostly through digital channels. The challenging part was, and still is, how the sessions can prepare students for practical exams. In-class lab sessions are recommended to make sure students not only get more proficient in the use of gem testing equipment and are trained in observation protocols, but also have access to a relevant and extensive collection of reference samples selected specifically for the purpose of teaching. The more stones a student can observe, the better.

Online education has been delivered in many formats through various platforms, from simple text and photos (and/ or video) to more complex interactive e-learning tools including presentations with voiceover, audio podcasts, videos or interactive systems, as non-synchronic sessions. Synchronic classes seem to be gaining popularity, partially due to the habits created during the Covid-19 lockdown. In spite of the convenience of the e-learning solutions available, having access to adequate study samples and a tutor to guide students through the protocols and observations are critical for a gemologist’s training. Although some organizations provide study samples to distance-learning students, their number may not be comparable to those available in a lab class.

Advanced Gemology Training

The complexity of today’s gemology has placed it much closer to science than ever before. Aside from gem identification, labs now include detection of treatments, identification of modern synthetics, accurate chemical fingerprinting, determination of major to trace elements (including isotopes), support for origin determination opinions. The collection and interpretation of such data calls for an advanced knowledge base, namely a Ph.D. in material sciences, solid-state physics and/or chemistry. To provide scientific knowledge to gemologists, the University of Nantes began offering the DUG (Diplôme d’Université de Gemmologie) in 1983, under the supervision of Professor Emmanuel Fritsch. The program focuses on advanced analytical and spectroscopic methods for laboratory gemologists. With a much shorter duration, the Swiss Gemmological Institute (SSEF) offers advanced and scientific gemology courses to complement the classical gemology education offered in most schools.

Read, Read, Read

Before the Internet, information was accessible in books, trade magazines, and in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Books written by pioneers such as Robert Webster (Gems), Richard T. Liddicoat (Handbook of Gem Identification), Basil Anderson (Gem Testing), Peter Read (Beginner’s Guide to Gemmology), Antoinette Matlins (Gem Identification Made Easy), and Edward Gübelin and John Koivula (Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones) are a few iconic titles that continue to serve gemological education.

Libraries such as GIA’s Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library (in Carlsbad, California) have thousands of books and periodicals that are accessible locally and online. In Europe, the library of L’École, the School of Jewellery Arts by Van Cleef & Arpels in Paris and the vast Sir James Walton library at Gem-A in London are two important repositories.

Many titles have become available as e-books or pdf files and an increasing number of out-of-print gem-related publications are available for free online.

From a periodical perspective, the first major gemology trade magazine was GIA’S Gems & Gemology in 1934, which evolved into a peer-reviewed journal. Current and past issues are now freely distributed online. The Journal of Gemmology, published by Gem-A since 1947, is the scientific voice of the association and also recently became a peer-reviewed journal. Interestingly, these two gemological journals are published by gemological education organizations, demonstrating that science and cutting-edge education go hand-in-hand.

Other magazines are also valuable resources, among them is InColor magazine under the editorial guidance of Jean-Claude Michelou. It covers topics from mining and geology, to gemology, design, and retail. A few other titles include The Australian Gemmologist (since 1958), Revue de Gemmologie (since 1965), Journal of the HK Gemmological Association, and the historic Lapidary Journal (since 1947). More recently, other titles are SSEF’s Facette, ICA GemLab’s Gamma, and Revista Italiana di Gemmologia. Gemology requires continuous education; Reading periodicals and books is definitely a must.

Symposia

Educational opportunities are also offered through global symposia and congresses with expert presentations, poster sessions, published proceedings, recorded sessions available online, and networking. Among these events are: GIA’s Symposia, since 1982; Gem-A’s annual conference; the Scottish Gemmological Conference, the Rendezvous Gemmologiques in Paris; Gem Talks organized by the Istituto Gemologico Italiano at VicenzaOro; GIT’s International Gem and Jewelry Conferences in Bangkok, the Mediterranean Gemmological and Jewellery Conference; the Sinkankas Symposium; FEEG’s annual Symposium,

AGTA’s gem show conference program, ICA’s biennial congresses; and a variety of national and regional gemological associations and alumni events that take place across the globe.

Field Trips

Gemologist-guided travel to remote mining areas was on the rise before the Covid-19 lockdown. Mine visits were typically organized as pre or post-symposia activities, but were also organized by gem schools, such the traditional Gem-A trip to Idar-Oberstein, the AIGS trips to Mogok and others by the Association Française de Gemmologie. Gem tourism was also a reality in Minas Gerais, Brazil, organized by Brazil Gem Safari, or in Portugal with guided tours to jewelry museums. The popularity of field gemology encouraged by Vincent Pardieu has created a wider demand for small organized group visits to mining and manufacturing areas.

Social Media

The Internet revolution made information easily accessible. Terabytes of material in archived books, journals, research papers, videos, podcasts, and websites are now available to students and researchers. But, even more terabytes of low-quality, erroneous, and non-verified information is also found online. The social media and blog worlds enable high-quality information, produced by knowledgeable peers, and low-quality information, produced with no accurate sources, to be shared in the same virtual space.

The key to properly using social media and the Internet to collect and use relevant information as an educational resource is to understand how to validate the sources for their intellectual and scientific qualities. Once that is filtered, a whole world of excellent LinkedIn profiles, Instagram feeds, Facebook pages, YouTube channels, gemological blogs, and Twitter accounts are available for self-education.

The Novel Coronavirus Effect

The Covid-19 pandemic shut down many colleagues and students in the gem and jewelry industry. While the lockdown caused distress across the supply chain, it triggered the creation of a gem and jewelry online entertainment initiative, which is also educational. Beginning in mid-March, the author began hosting the Home Gemmology Webinar Program, which then got the support of CIBJO after its 6th session. Other webinars include Gem-A’s gemology series, AIGS’ Thailand Gem Trips program, GIA’s Knowledge Sessions, Justin Prim’s Institute of Gem Training, AGAT Live with Laurent Massi, and the extensive Gemflix webinar program.

The lockdown has made distance education a widely accepted solution. The collaborative e-learning platforms, already being used by the major educational organizations, have been expanded to reach out to students and trainees.

Rui Galopim de Carvalho FGA DGA is a Gem Education Consultant with a vast experience in course development and content creation and also an in-class and remote tutor for groups or in one-on-one sessions. As an international lecturer, Rui has traveled the world and surfed the digital ecosystem giving talks in various aspects of gemmology, gem history and jewellery. During the COVID-19 lockdown his Home Gemmology webinars were popular entertainment and educational free events, having had the support of CIBJO - The World Jewellery Confederation.