Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

A promising tool to help develop gem-producing areas led to the creation of an award-winning documentary.

For some years now, many people in the gem industry have tried to improve the lives of local communities near gem producing areas. Among the most popular types of projects involved those designed to increase the knowledge of gem miners and their families so they could better understand the potential of the gems they were producing.

Several other projects provided tools and training to extract and cut the gems. Donating cutting machines and/or setting up lapidary offices helped change these communities.

In places such as Madagascar, I witnessed, in 2005, a gem cutting center and a gemology school being set up with significant support from the World Bank. With regular trips to Madagascar afterwards, some changes in the Malagasy gem trading industry were evident. Cutting at local gem shops improved, as many young Malagasy (and a few foreigners) received training. Still, though, after 15 years, the gem industry in Madagascar has not changed all that much. With few exceptions, it is still dominated by foreign buyers (mostly from Sri Lanka, Thailand, and West Africa) coming to purchase rough.

Over the years, I regularly met several people who studied gem cutting at the IGM. They stated that, despite the useful knowledge they had acquired, they were struggling. The reason was simple. Madagascar was not really on the map for people buying faceted gemstones. Only foreign buyers looking for rough were coming. Because the foreigners had good markets back home, they could pay better prices in Madagascar than local cutters. As a result, local cutters struggled to get good rough and good prices for their products, and most stopped cutting and changed businesses.

If the industry really wanted to help local mining communities, it had to find something more efficient than merely setting up gem-cutting centers or distributing books about gemology.

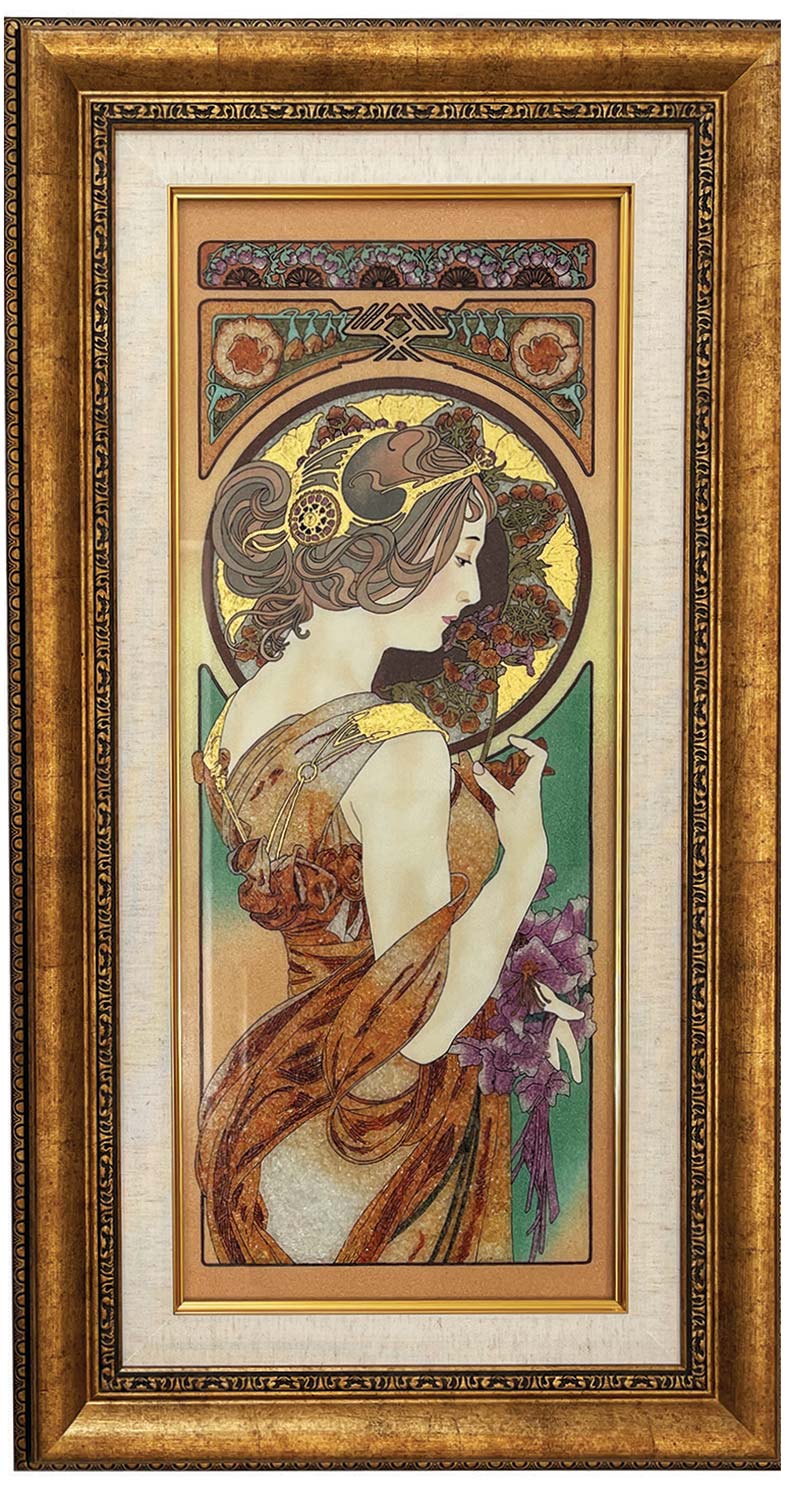

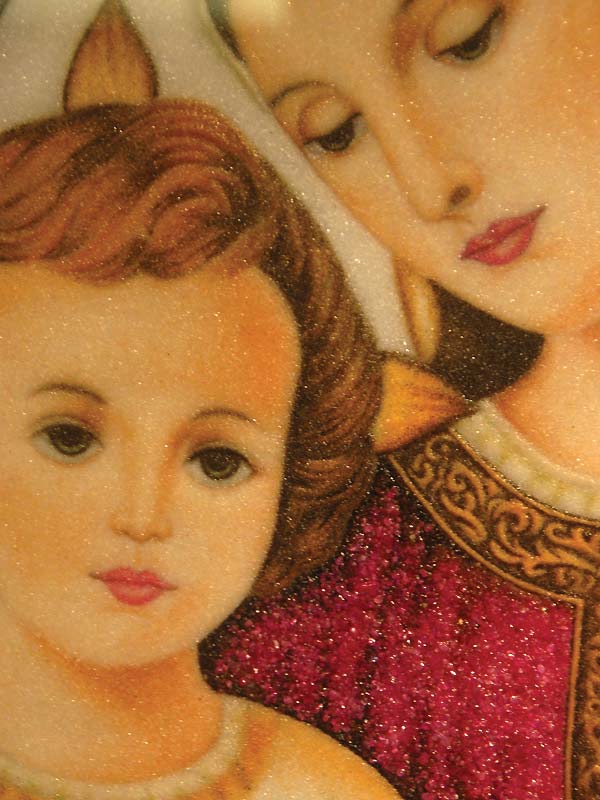

Having traveled regularly to gem-producing areas around the world for the past 20 years, it was clear to me that good intentions were not enough. If the industry really wanted to help local mining communities, it had to find something more efficient than merely setting up gem-cutting centers or distributing books about gemology. After few visits to Vietnam and Myanmar, I realized that gem paintings could be a very efficient tool to help local industries.

Since 2005, in the ruby mines near Yen The in the Luc Yen district of Vietnam, the miners collected not only colorful transparent gem material but also everything else. One day I asked: Who was buying this low-quality material? One of the miners replied, “I sell the material to people doing gem paintings.” And at a good price? I asked. “Well, they don’t pay much but what I get is enough to keep mining,” was the answer.

That day, with that simple answer, it was obvious that gem paintings were the backbone of the gem industry in North Vietnam. Thanks to this handicraft, local small-scale miners receive the daily income they need to cover their mining expenses, allowing them to sometimes find gems that are large, colorful, and transparent enough to be faceted.

Visiting the Mogok gem area in Myanmar in 2014, it was surprising to see how much it had changed since my last visit in 2004. While good stones were difficult to find, the small-stone and low-quality stone markets were very active.

Such a change from the past, when nearly everything that was not a fine ruby was rejected since there was no market for it. What were the changes? Gem paintings were the main new endeavors. Since their introduction in Mogok, more than 50 family gem-painting factories were working.

It was obvious that gem paintings were the backbone of the gem industry in North Vietnam.

In the past, the Burmese believed that it was unlucky to crush low-quality gems because of the spirits that inhabited them. Now, they are beginning to think differently. Like in Vietnam, gem painters provided a good market for the people who collected stones from the reject piles of the large mining operations. In Mogok, the Kanase people did this work, and with the arrival of gem painting, the kanase were busier than ever. They collected all types of material, which they sorted at home and sold everything unsuitable for cutting to the numerous gem painting operations in town.

The great attraction of gem painting compared to lapidary work is that gem painters don’t need foreign buyers in order to have a successful business. Although gem painters were selling some of their products to tourists, most of the companies (in Myanmar and Vietnam) were selling their paintings in the local market. Some motifs were religious (from simple Islamic or Chinese calligraphy to complicated portraits), while others were landscapes, historical or nationalistic illustrations such as propaganda posters, or portraits of Ho Chi Minh. Gem paintings can be used to decorate homes, hotels, official and religious buildings, and of course, can be sold as souvenirs to visiting tourists or exported to foreign markets.

Gem paintings are, however, not that new. The author first saw a few in 2002 while working for Mr. Henry Ho in Bangkok. He said that his family introduced gem paintings into Thailand in the 1980s after a visit to Jaipur, India. But they remained quite anecdotal in Thailand despite a few incredible factories such as Than Thong Art. Why? I wondered.

I learned that the likely reason for the boom in Vietnamese and Burmese gem paintings is because they were introduced in the gem producing areas rather than in the main cities. Being close to the mines makes it easy for the painters to get cheap rough to crush in order to make the powders they need. Because low-quality rough is easily available, the technique can spread rapidly, with families following other families who had created profitable businesses.

The benefits of gem painting went beyond the painters. Miners were able to get a regular income from the low-quality stones, thus allowing them to continue searching for quality gems. This in turn, allowed for more mining and thus the discovery of more quality and even exceptional gems. Jobs were created all around, thus helping to eliminate poverty.

Over the years, impressed by an industry that produced beautiful objects, the author regularly talked about gem paintings to industry friends, as well as showing them to people accompanying him on trips to Vietnam or Mogok.

It’s easy to imagine the benefits of introducing gem painting to other producing areas such as Madagascar, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Afghanistan and even Greenland. Yet, when bringing it up to the corporate types, the reply is the same: “It sounds great, but can you provide us with documentation to support this interesting idea?” Alas, this information was scarce.

In 2018, while planning a visit to Vietnam to collect reference samples for the DANAT Lab, I invited my old friend Philippe Brunot—the author of Follow the Zebra, a documentary about small-scale miners in East Africa—to come along, and make a 20-minute documentary about gem paintings. We interviewed people in Thailand and Vietnam and completed the documentary on time for the 2019 ICA Congress in Bangkok.

Thanks to gem painting, small-scale miners get the needed daily income to cover mining expenses, allowing themto perhaps find gems that are large, colorful, and transparent enough to be faceted.

Called Gem Painting, it was presented as an illustration of the author’s talk about how the industry can help develop gem-producing areas. It was well received by industry members, and to give even more exposure to this beautiful handicraft, we entered the film in several festivals. It won the award for the Best Short Documentary at the Paris Film Festival in 2021.

Hopefully, this award will help raise the awareness about this wonderful technique and how it can be a promising tool to help develop gem-producing areas around the world.

Gem Painting is available for viewing on Youtube on the Field Gemology channel.

Gem paintings is a rather old technique that is not very well known but that have in our opinion a great potential. They were introduced to the Yen The area in Vietnam during the 1990’s by few ingenious local people who were inspired by what people were doing in Thailand.

In this documentary we interviewed some gem painters both in Thailand and in Vietnam and we decided to let them speak about their wonderful art.

We hope that this short documentary will be able to inspire people willing to develop the gem industry around the world, or to provide alternative livelihoods to people around places where gems are produced. As we saw in Vietnam, there is a big market for “gem paintings”. Gem paintings can be used to decorate hotels, religious or official buildings, offices, houses, shops, etc.. They can also be sold as souvenirs for visiting tourists or used as export products.

Many thanks to the people who welcomed us in Thailand and Vietnam and more particularly to Wanlaya Suwan from Thang Thong art in Thailand and Mai Tran and Geir Atle Gussiås in Vietnam.

Special thanks also to my team: First to Philippe Brunot who did a wonderful job directing and filming that documentary and to my old friend Thi Hoa Le for her support with translations, then to Didier Barriere and Anthony Methez for their additional images and also to my expedition guests (Raphaelle Cousteix, Circé Simonet, Katherine Andrews, Thierry Fontich, Yann Even Bouten, Angir Jp) for their support and understanding.

Please ENJOY, & Do not hesitate to SHARE, and SUBSCRIBE!