Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

The story of Richard Hughes’ four-decade adventure with jade, from Burma’s jadeite mines to China’s classic mutton-fat nephrite deposits at Hetian, Xinjiang Province. The work of China’s modern jade carving masters is also discussed.

On the road to Mandalay, Where the flyin’-fishes play, An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

Rudyard Kipling, Mandalay

My journey into jade started at age 18, when a friend invited me to travel with him to Europe. One thing led to another; Europe became Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and India, and by 1977, I found myself in the dusty upcountry town of Mandalay, Burma. It was there that I saw my first piece of jade. I was smitten and resolved then and there to become a jade trader. Why, I’m not quite sure. I guess it just seemed so damned exotic. Little did I know that I would have a destiny with jade. Now – 43 years on – I’ve spent much of my life working with this stone. As I look back upon that road, I am still stunned at how every twist and turn revealed new secrets, new adventures, new friends. What follows is my story of a lifetime spent in pursuit of heaven.

Road Trips

By 1979, I was living in Bangkok and studying gemology. I ad found my calling. This was a subject so fascinating, I lived, breathed every bit I could get, from books to magazines to the stories shared with me by colleagues and mentors. But there is only so much one can learn staying in place. So, I traveled. Burma, India, Sri Lanka, wherever there were gems, I went. Many journeys were made to the Thai/Burmese border outpost of Mae Sot, for this was a major entry point for gems squeezing out to freedom. As I closed my eyes at night, it was not sugarplums, but dancing rubies, sapphires, spinels and jades that moved through my head. My dream was to visit the sources of these gems. But that would have to wait.

Maori Greenstone

In the early 1990s, I was invited to lecture in New Zealand. One day walking down an Auckland street, I happened upon a small shop selling jade. At the time I had only a cursory knowledge of what the Maori’s called pounamu, a green nephrite from the South Island. But in this little shop, I discovered another world, the most beautiful carved jades I had ever laid eyes upon. As I purchased one for my wife, Wimon, the shop assistant told me that I had made an excellent choice, relating that the piece had been carved by none other than Donn Salt, New Zealand’s premier jade carver. I exited not just with the carving, but also with a book written by Salt celebrating New Zealand’s talented carvers. Their work was so fresh and contemporary, it left a lasting impression on me.

Opportune

That opportunity finally happened in 1996. Coming back to Mandalay from Mogok, I asked a military officer if my friend and I could visit the jade mines. When he said yes, I had to stop myself from immediately kissing his feet.

The result was a series of epic journeys to the jade mines, opening to the Western gemological world a place that had not been visited by outsiders since Eduard Gübelin in the early 1960s. From that point on, I was on a mission to learn as much as possible about this incredible stone we call jade.

Defining Jade – More Than Just a Stone

Certain natural materials have been collected and admired by humans since the dawn of time. Gold is noted for its rarity, malleability and ability to avoid oxidation.

For these reasons, it has been prized by virtually all cultures and peoples. But while gold has been highly sought after, it did not attain a status of supreme reverence. For that type of adulation, we must look to another product from the earthly realm: jade.

Yü, the Chinese word for jade, is one of the oldest in the Chinese language with its pictograph (玉) said to have originated in 2950 BC, when the transition from knotted cords to written signs occurred. The pictograph represents three pieces of jade, pierced and threaded with a string that together represent virtue, beauty and rarity. The addition of the dian stroke (dot) completes the character and distinguishes it from 王 (wăng), the character for emperor. Just how fundamental this character is in the Chinese language is illustrated by the modern form of the character for kingdom, 国 (guó), which has the jade character enclosed in a boundary to represent “country.” Thus the jade character is a component of the name for the country of China: Zhongguo, 中国. The English name jade comes from the Spanish piedra de ijada, literally “stone of the flank of the lower back,” from the Mesoamerican native belief that jade combats kidney ailments.

A Tale of Two Gems

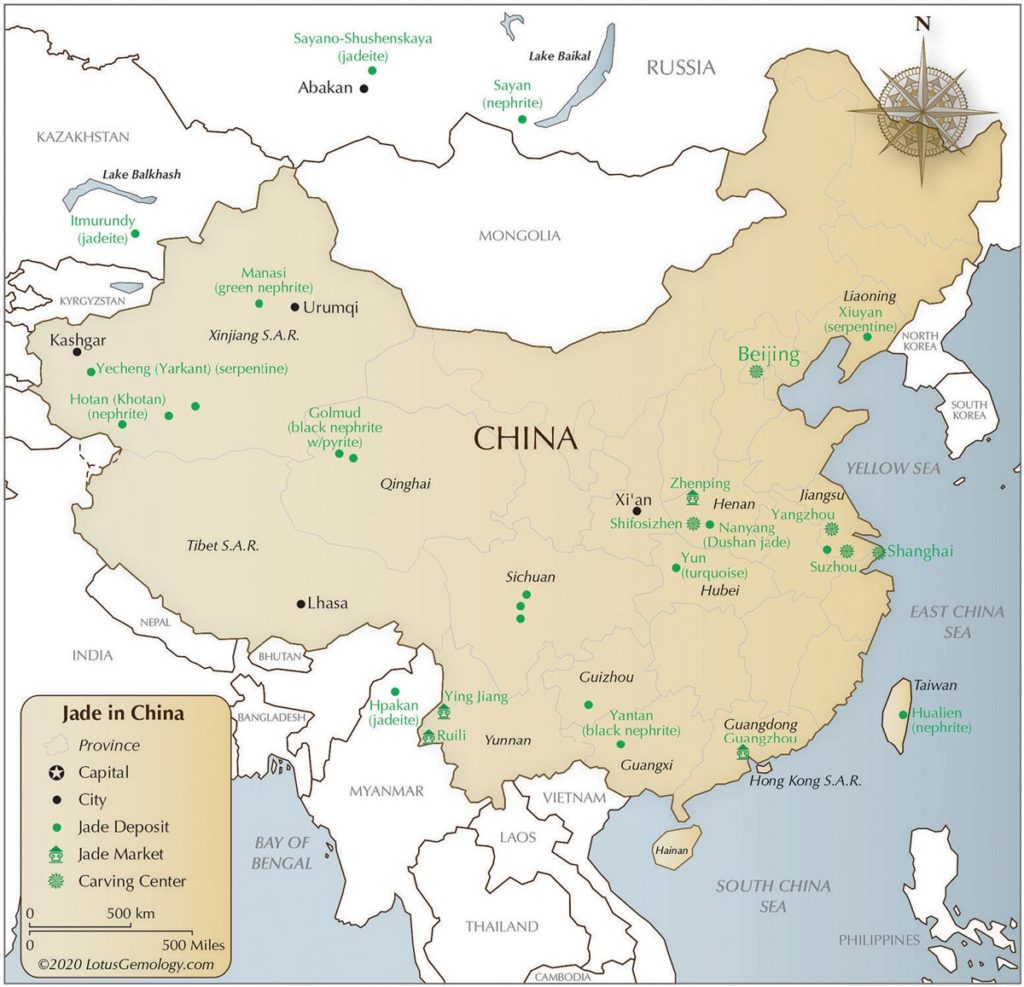

For some eight thousand years, jade has been treasured by the Chinese. While there are a number of different sources in China, the most important are the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black (a.k.a. Green) Jade (Karakash) Rivers near the town of Hetian (和田; a.k.a. Khotan) in western China’s Xinjiang Province (Chinese Turkestan).

From these deposits comes a creamy white to greenish stone, with the most valuable being pure white, termed “mutton fat.” Sitting astride one of the old Silk Roads, it first entered China proper via traders from Central Asia. While the discovery of jadeite jade in Myanmar dates back to the 6th Century ad or earlier, and its first entry into China was dated by British Sinologist William Warry in the 13th Century (Hertz, 1912), it did not come into prominence until the Qing Dynasty (1644–1914).

When Emperor Qianlong saw a piece of this white-to-bright green jade, he was besotted. Learning it came from a wild country south of Yunnan, he sent columns of troops down to secure a supply. But even the crack Chinese armies were no match for the difficult terrain and fierce Kachin hill people. They returned empty handed, beaten back by malaria, mud and tribespeople who toyed with the outsiders from the north. Thereafter, Chinese traders generally never attempted to venture into the hills to the mines, content to deal with the Kachin on the comparatively tranquil plains at Mogaung.

The Chinese understood this material was different from the Hetian jade, and named the vivid green variety fei cui (翡翠) or kingfisher jade, due to its resemblance to the color of the feathers of the kingfisher bird.

Mutton-Fat Jade

In the Western world, the term jade today is used for two different rocks, jadeite and nephrite. However, in China, traditionally, there were four “great jades”: Hetian jade (nephrite; Xinjiang province), Xiuyan jade (serpentine; Xiuyan, Liaoning province), Dushan jade (rock mixture of anorthite, zoisite and hornblende; Nanyang, Henan province) and turquoise (Yun, Hubei province). Considering just jadeite and nephrite, while each of these cousins shares certain characteristics, in other ways, they could not be less alike. Yin/Yang. They are two entirely different bridges to heaven.

Although I have been involved with jade since 1977, it was only when I visited China’s famous Guangzhou jade market in 2009 that I was exposed to Chinese mutton-fat jade (nephrite). It was love at first sight; now I better understood the deeper attraction of jade.

While I once believed that only jadeite had high value as a gem material, this opinion was born of ignorance. The white Chinese nephrite is a lovely gem material possessing a sublime beauty all its own and today fetches prices that sometimes compete with the finest imperial jadeite.

Today, this “mutton-fat” jade from Hetian is considered to be the finest in the world, with the highest prices being paid for white stones from the rivers. Material quarried nearby from hard rock mines is much less valuable as it may have hidden cracks and it lacks the natural surface staining of the river stones that is prized by carvers.

Whereas jadeite is lipsticked gloss and neon, the beauty of Chinese nephrite involves a far different experience, where depth and feeling rule. Having now experienced both worlds, I must say that, as I grow older, I tend to be drawn more to the world of Hetian jade. Burmese jadeite is bikini eye candy. In contrast, Hetian jade involves hidden beauty, and thus discovered via sweet caress and touch. Even the manner in which the gems are displayed is radically different.

Jadeite struts her stuff under gaudy lights surrounded by the sparkle of diamonds; in contrast, nephrite is placed in front of the public like fine art, with dark backgrounds and generous space, befitting a stone that the Chinese consider more valuable than silver or gold – the most precious substance on Earth, literally, the Middle Kingdom’s bridge to heaven.

High Nubility

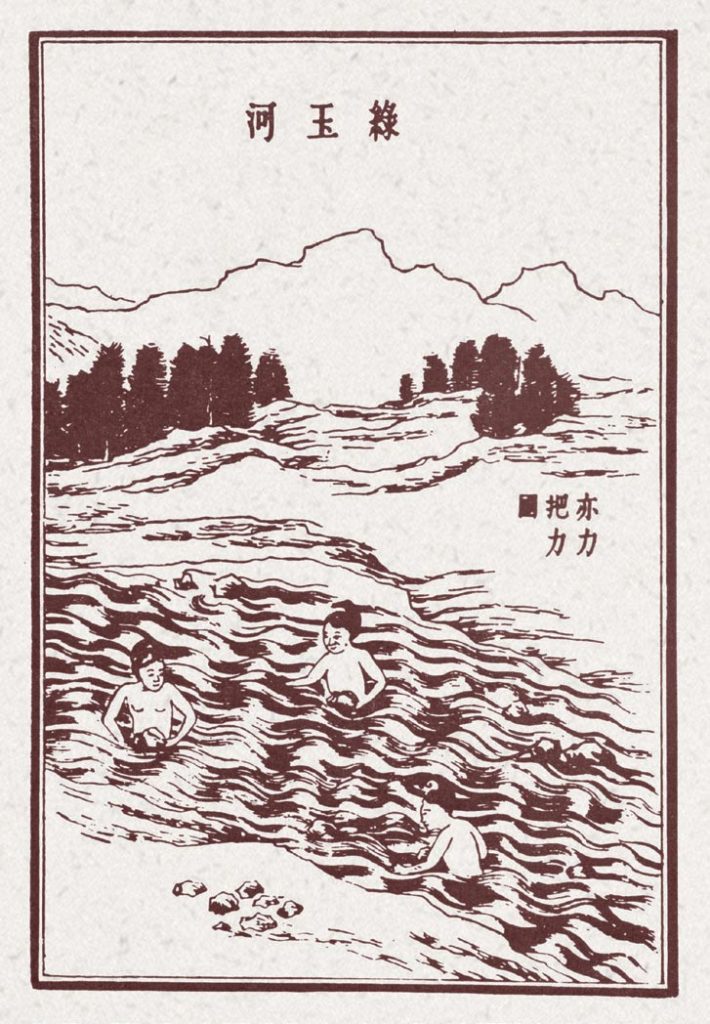

Ever since I discovered Chinese mutton-fat jade, I had a desire to visit the source. Hetian is located in western China just north of the Kunlun mountains that separate China from Pakistan and India. According to Chinese lore, jade is masculine. Following this logic, to attract it requires something feminine.

For example, it was told that jade could be caught if naked virgins were sent into the rivers on moonlit autumn nights.

Thus, it was that, in the summer of 2017, I set out for Hetian with the highest of anticipation, visions of virgins dancing in my head. Alas, upon arrival, there were no naked nubiles at the river, just one old man with a shovel. When we asked if he had found any jade, he reached down into his bag and produced a boulder. We quickly bought it.

Booked

I have a terminal love of books and whenever I travel, I try to make time for what some refer to as a “gentile madness.” The first time I visited Shanghai in 2011, I found Fuzhou Rd, a lovely street with several great bookstores. Several years later, I was back in Shanghai at the invitation of Tongji University’s “Adam” Zhou Zhengyu. I mentioned to Adam that I wanted to go back to Fuzhou Rd. He said I should first visit the Tongji Bookstore. That turned out to be his office and, as I departed, I was overloaded with kilos of books on Chinese jade that he had gifted me. Back in Bangkok, I opened them up and was completely floored. Expecting to see scholarly reproductions of older jades, I was amazed to discover page after page of stunning contemporary designs.

YYYYEEESSSS!!!! When I later asked Adam if he could arrange visits to meet some of these carvers he slyly smiled and said: “Of course. They are my friends.”

This is how I came to meet China’s new jade masters, people like Ma Hong Wei, who makes jade reproductions of ancient Chinese bronzes, Yu Ting, who specializes in eggshell thin carvings and Yang Xi, whose negative space works are as fresh as any contemporary art in the world. But the carver I most wanted to meet was Wu Desheng. His flowing nudes were the ones that I was most taken by.

Wu Desheng is perhaps China’s most famous contemporary jade master and has a studio on the outskirts of Shanghai. Built on a large tract of land, it is a re-creation of a traditional Chinese home, with a square central courtyard. Master Wu was a gracious host and gave us a full tour of his compound, with various workshops filled with people carving jade. As we were leaving, Wu casually mentioned that, if I had a piece of jade, he would carve it for us.

YYYYEEESSSS!!!! After kissing his feet, I quickly whipped out the jade boulder we had purchased in Hetian the previous year before he could change his mind. Game on.

Every year, Suzhou hosts an international carving competition, where China’s best face off against the world. I was honored to attend and speak at the April 2019 event. Donn Salt had come up from New Zealand and as we wandered the exhibit halls, he remarked that he felt like a young schoolboy. Such is the quality of jade carving in China today that one look will have you forgetting every tired Guanyin statue you’ve ever seen.

In September 2019, Adam invited me to visit one of China’s most famous jade deposits in Liaoning Province in the northeast. There we visited the studio of Master Tangshuai, who creates organic flowing carvings in serpentine. Returning to Shanghai, we learned that Master Wu had finished the carving of my boulder, and so once again visited his compound. He brought out a small custom-made box and presented it to me.

“Imperial” Jade

Today the term “imperial jade” is generally applied to the finest qualities of green jadeite jade from Myanmar. But readers may be surprised to learn that the phrase was apparently invented not by the Chinese, but in the West. The first known instance of the term “imperial jade” in a European language can be found in the noted French ceramic expert, Albert Jacquemart’s description of the jade collection of the Duke de Morny, published in 1864:

…Above all, the two rare species are the orange jade, of which we can easily count the few examples gathered in Europe, and the imperial jade, invaluable gem, worthy of competing with certain premium emeralds. When it is green, and which, varied in green and white, produces an effect superior to that of the richest agates. Almost unknown before our expedition [the French/British sacking of the Summer Palace in 1860] from China, this stone has only arrived in small samples since.

– Albert Jacquemart

“Collection d’objets d’art de M. le Duc de Morny” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1864

From the phrasing Jacquemart uses (the imperial jade), it suggests the term was not necessarily coined by him, but perhaps already in use. Mark Chou (Dictionary of Jade Nomenclature, 1987) has a much later definition of imperial jade:

In strict meaning, it means: The choicest jade to be deserved to be collected by the Emperor. This phrase has been undoubtedly originated from [the] western world.

1st sense. If applied and usually to Jadeite, it must be translucent and transparent with the finest emerald green color and is never found in large masses… Among the Chinese it is Bo Li Cui.

2nd sense. If applied, but rarely to nephrite, stands for the finest mutton fat jade, called by the Chinese Guo Yu, Ning Zhi Yu, Yang Zhi Bai Yu, and Zhi Yu. It is also known with [the] western name of Imperial White Jade.

Touched by Jade

Jade is the most sumptuous jewel against a woman’s flesh.

Pearl Buck

My journey with jade had taken me around the world, to five continents and dozens of countries over four decades. I pondered all I had seen chasing this magical stone. Yes, there were some disappointments. I hadn’t found the moonlit virgins in the river. But I had visited so many places, had so many great adventures, made so many new friends.

As I opened the box that Master Wu had presented me, I touched something smooth, creamy, almost like a woman’s skin. Bringing Wu’s creation into the light, for the first time, I truly understood what jade means to the Chinese. In that box lay my mystical virgin from the river. I was holding heaven in the palm of my hand.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following people for spending the time to introduce him to jade: Adam Zhou Zhengyu and Jason C.H. Kao of Shanghai’s Tongji University, Master Wu Desheng, Lin Tze-Chuan. Thanks to the world’s Master Carvers for letting us into their hearts and studios, including Cuilei, Donn Salt, Fan Junmin, Georg Schmerholz, Liu Zhongrong, Ma Hong Wei, Pang Ran, Qiu Qijin, Ru Yuefeng, Tang Shuai, Wang Dehai, Wu Desheng, Yang Guang, Yang Xi, Yu Ting and Zhai Yiwei. Thanks also to Leong, Vivian Deng, Lancie Deng, Zhao Wenbi & Jin Jiyang, Cooper Ke, Sun Yunwu, Ms. Lina, Ms. Li and Mr. Tong (Zhong Wei Co.) for sponsoring some of our travels.

References and Further Reading

- Chou, M. (1987) Dictionary of Jade Nomenclature. Hong Kong, privately published, 150 pp.

- Goette, J. (n.d., ca. 1936–37) Jade Lore. New York, Reynal and Hitchcock, 321 pp.; [1976 edition by Ars Ceramica with an introduction by William C. Hu].

- Gump, R. (1962) Jade: Stone of Heaven. Garden City, NY, Doubleday & Co., 260 pp.

- Jacquemart, A. (1863–64) Collection d’objets d’art de M. le Duc de Morny. Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Vol. 15, 1 November, pp. 393– 419; Vol. 16, 1 January, pp. 28–50.

- Laufer, B. (1912) Jade: A Study in Chinese Archaeology and Religion. Chicago, Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 154, Anthropological Series, Vol. X, 2nd ed. reprinted by Westwood Press, 1946; Dover, 1974, 370 pp.

- Salt, D. (1992) Stone, Bone and Jade: 24 New Zealand Artists. Auckland, David Bateman, 95 pp.

- Sung, Ying-hsing (1966) T’ien-Kung K’Ai-Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. trans. by Sun, E.Z. and Sun, S.-C., University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 372 pp.