Estimated reading time: 16 minutes

In all of recorded history, there is no greater example of a more intimate relationship between a stone and a people than that of jade and China. Within the Middle Kingdom, jade has been loved, appreciated, collected and handed down for nearly 8000 years. Its influence extends from the Chinese language and arts, through poetry and novels, through modern literature, opera and film.

In the development of human society, no other culture approached China in equating jade with human character, personality and human nature. To the Chinese, jade transcended the material world of things, entering a spiritual realm, thus influencing and becoming the carrier of Oriental philosophy.

The Four Great Jades

It is said in China that the country has had “four great jades” since ancient times. This refers to the four kinds of jade that were most commonly used and had the highest status in Chinese history. These were:

● Hetian jade (nephrite) from Hetian (a.k.a. Hotan, Khotan), Xinjiang Province

● Xiuyan jade (serpentine) from Xiuyan County, Liaoning Province

● Dushan jade from Nanyang City, Henan Province. This is a rock composed mainly of anorthite and zoisite, with minor hornblende and variable amounts of accessory minerals such as chrome-bearing micas, chromian epidote, prehnite, titanite, tourmaline and volkonskoite, which impart various shades of green colors

● Turquoise from Yunxian County, Hubei Province

From this, one can see that “jade” in the Chinese mind refers to not only jadeite jade in Myanmar and Hetian (nephrite) jade, but also other rock/mineral aggregates that have similar characteristics (beauty and toughness, coupled with the ability to take a fine polish).

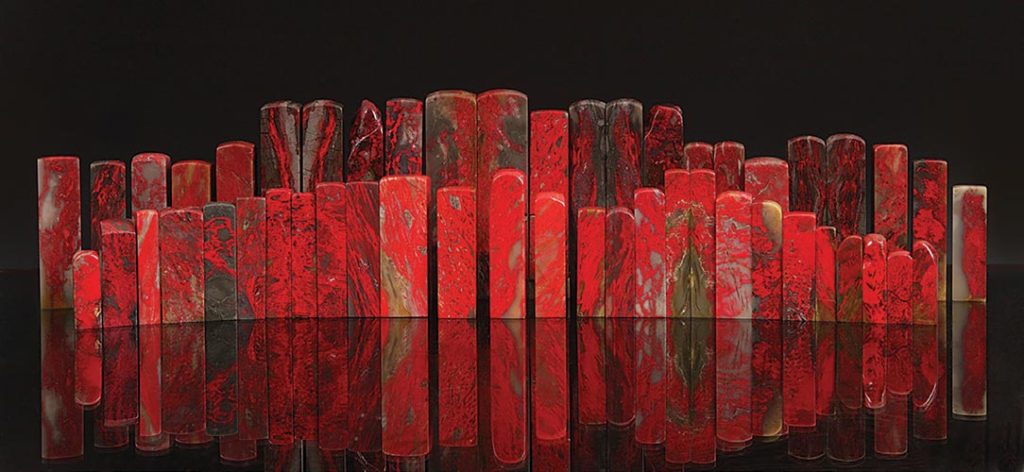

Xu Shen’s Shuowen Jiezi [Interpretation of Words and Texts] in the Eastern Han Dynasty [121 ce]1 interprets “jade” as the “beautiful stone,” thus expanding jade’s definition to encompass seal stones such as “tianhuang stone” and “chickenblood stone” (dickite with cinnabar). Among them, Hetian jade is honored as “Imperial jade” and is considered China’s National Jade, despite the fact that today the top price of jadeite has exceeded that of Hetian jade.

Hetian jade, pure white with muted luster, is also called mutton-fat white jade in China. The Hetian area, known as Khotan in ancient times, originally came from the word Godana or Khotana, which meant “Breast of the Earth.” In Tibetan, it means “Land of Cows,” but because that sounded similar to yü in Chinese, the Chinese started using the jade character, Yu-tien. In the early Qing Dynasty, Khotan (于阗) was changed to Hotan (和阗). In 1959, the Chinese government changed Hotan (和阗) to Hetian (和田), the name by which it is known today.

The earliest written record of Hetian jade is from Sima Qian [135–86 BCE] in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). That book contains a passage that reads: “The Han emissary is looking for the source of the river from the mountains at Khotan, where many jades are found.” – Sima Qian [135–86 BCE], Records of the Grand Historian.

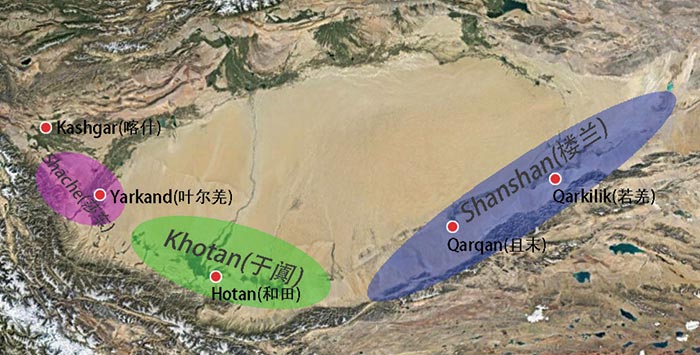

Later, in the Eastern Han Dynasty, Ban Gu (32–92 ce) speaks about Shache (莎车), which is located between Hetian and Kashgar: “The capital of the kingdom of Sha–keu is the city of Sha–keu… There is an Iron Mountain (which) produces blue-green jade.” – Ban Gu [32–92 ce], The History of the Han Dynasty.

These two brief mentions provide clear evidence that jades were produced in Shache and Khotan states, in what is now Xinjiang over two thousand years ago.

China’s original “four famous jades.”

A Narrow Definition Broadens with Time

At first, people named jade after the mountain where it was produced, e.g. Kunlun jade. In 1759, Emperor Qianlong appointed a minister of Hotan with the chief aim of organizing mining so that nephrite production could flow into the palace. From this point on, this kind of jade began to be called Hetian jade. For an extremely long period, the name “Hetian jade” carried a strict implication of origin. Only the tremolite jade produced in the Hetian region and the Kunlun Mountains nearby could be called Hetian jade.

However, with the passage of time, this narrow definition broadened. Tremolite jade was found in a narrow strip stretching about 1500 kilometers along the northern slope of Kunlun Mountains from Tashkurgan to Ruoqiang. Gradually, tremolite jade in Xinjiang, from the Kunlun Mountain to the Altun Mountain area, all came to be called Hetian jade.

Responding to this, in 2010, the Chinese government revised the national standard of “Gem and Jade Names,” removing geographical origin from the definition. Today, no matter what the source, as long as the main component is tremolite/actinolite, it can legally be called Hetian jade. Thus actinolite/tremolite jade from Xinjiang and Qinghai, or from Russia, Canada and South Korea, qualifies as Hetian jade.

Mineralogical Composition

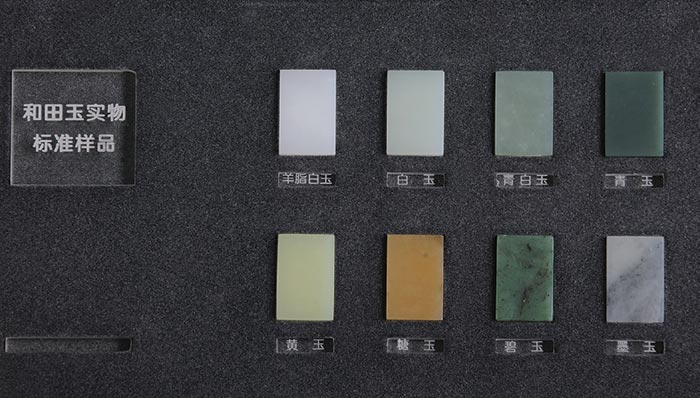

Hetian jade is a rock where the main mineral components fall into the actinolite-tremolite solid solution series of the amphibole group. White and light colored Hetian jade is mainly tremolite, while dark green Hetian jade is mainly actinolite. Some extremely dark Hetian jade is called black jade, and its mineral composition is mainly ferro-actinolite.

Chemical analysis shows that the composition of Hetian jade is basically the same as actinolite-tremolite, and its common colors are white, cyan, green, yellow, brown and black. At present, we believe Fe2+ causes the cyan color; Cr and Ni play an important role in the emerald green variety; graphite inclusions produce the black coloration; it is generally believed that yellow and brown are related to Fe3+, but there is no conclusion on what causes the difference between yellow and brown tones of Hetian jade.

In addition, there are rare pink, blue and purple nephrites, and the causes of those colors is unknown.

95 Yutian Jade

Among the above varieties, the best white jade is said to be produced in Yutian County, Hetian District. In 1995, a batch of extraordinary quality was produced—pure white with tight structure. These became known as “95 Yutian jade” in the market. As of 2020, the rough price has exceeded US$200,000 per kilogram. Nephrite from the Lake Baikal area of Russian is considered second only to 95 Yutian jade.

Cyan Jade

In the past, the best cyan jade was thought to be produced in Tashkurgan (Xinjiang Province), but in recent years, Gulmud (Qinghai Province) has produced first-class cyan jade. Because of its fine smooth structure, it can be used to make eggshell-thin vessels with a thickness of less than 1 mm.

Dark Jade

The so-called “dark jade” is actually a dark green color found in Dahua area of Guangxi at the end of 2011. This material has excellent texture, which makes it great for carving. Because of the high Fe content (19–25%), it shows dark green and often contains pyrrhotite, similar to the copper censer material made in the Ming Dynasty of China, so it is often made into similar vessels, generous in size and of simple designs.

Black Jade

The best black jade is produced in the Hetian area of Xinjiang (the legendary Karakash, or “Black Jade River”). Black jade may be distributed either in spots or layers. Among them, graphite spots are often regarded as impurities, which reduce the value. In contrast, layered graphite is widely welcomed in the market because its clear color boundaries make for easier integration into finished carvings.

Hetian Jade Types

Hetian jade can be divided into four types, according to its occurrence.

Mountain Jade. Jade quarried directly from the primary deposit is called “Mountain Jade (山料).” Most of these deposits are layered ore veins and the extracted raw stone is generally found in the market as sharp angular shapes.

Mountain Water Jade. Weathered hillside deposits are called “Mountain Water Jade (山流水)” and are often located on hillsides or at the foot of the mountain below the primary deposits. These stones show rounded edges and corners due to short distances of transportation.

Placer (Zi) Jade. Jade from placer deposits is called “zi jade (子料),” which is the most valuable Hetian jade material. In the past, it was mainly excavated in the riverbeds of the White Jade (Baiyu or Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers at the foot of Kunlun Mountains in Hetian. Nowadays, it is mainly excavated in the river terraces and ancient riverbeds on both sides of the river.

Desert Jade. Jade from the Kunlun Mountains eventually reaches the edges of the Taklamakan Desert. Because of its long-term wind and sand erosion, the impure parts of the jade are completely removed and become the hardest Hetian jade material. The surfaces of the best desert jade resemble fish scales, but this is very rare. There is confusion over the name of this type. This material is called “gobi jade (戈壁料)” not because it comes from the Gobi Desert (which is to the north and east of the Taklamakan Desert), but because the term “gobi” in Chinese refers to a type of hard-gravel desert, instead of a sand-dune type desert.

Qualities

Color

Chen Renxi (1581–1636 CE) of the Ming Dynasty (1368– 1644 ce) compiled a complete history of China, the Qianqueju Series Books, incorporating the writings of many earlier historians. He wrote: “Jade has five colors, white, yellow and green and all are precious.”

Gao Lian (1573–1620 ce) of the same era further described that “sweet yellow is the most important color for jade, followed by mutton-fat white jade.” He also mentioned that yellow is the emperor’s royal color, and that the output of yellow nephrite is too rare to be used by the royal family. Because virtually no yellow nephrite could be found in the market, the palace utilized mutton-fat white nephrite for most carvings, causing its price to actually exceed that of yellow nephrite.

Generally, there are three criteria for color evaluation: hue, saturation, and tone. Hue refers to the position of a color on a color wheel, e.g. yellow, green, cyan, etc. Hues that are pure colors, without secondary modifiers, are generally preferred. Saturation refers to the intensity of the color. Tone refers to the lightness/ darkness of a color. White, gray and black are achromatic; they lack color, varying only in tone. Note that even the finest mutton-fat white Hetian jade generally has a subtle tint of color. The closer it is to pure white, the more desirable its color.

Structure

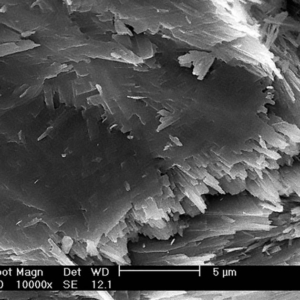

There are three aspects to judge Hetian jade’s structure: the first is the thickness of tremolite fibers. Generally, the finer the fibers, the higher the quality. The width of tremolite fibers in Hetian jade is usually less than 0.5 μm under SEM.

The second is the interlaced weaving angle between tremolite fibers. Generally, the larger the angle, the gentler the luster of Hetian jade will be. If fibers are parallel, a jade cat’s eye can be made by cutting a cabochon. Among nephrite jade cat’s eyes, the best quality comes from Sayan, Lake Baikal, Russia, followed by Hualian County in Taiwan.

Finally, the compactness of the inlay between the tremolite fibers is important. The lower the porosity, the better.

Clarity

There are many common included minerals in Hetian jade, which often appear in various colors and forms, so they are easy to observe with the naked eye.

Micro Raman spectroscopy has revealed that the white points and crumb structure are typically calcite, quartz or orthoclase. Pink crumbs have been found to be diopside, while most of the black impurities are graphite.

As previously mentioned, Hetian jade containing large amounts of graphite is also known as black jade. In recent years, pyrite and pyrrhotite have been found in cyan-colored nephrite from Xinjiang, Qinghai, Guangxi and other places, either in cubic crystal form or in filiform dissolution and impregnation structures.

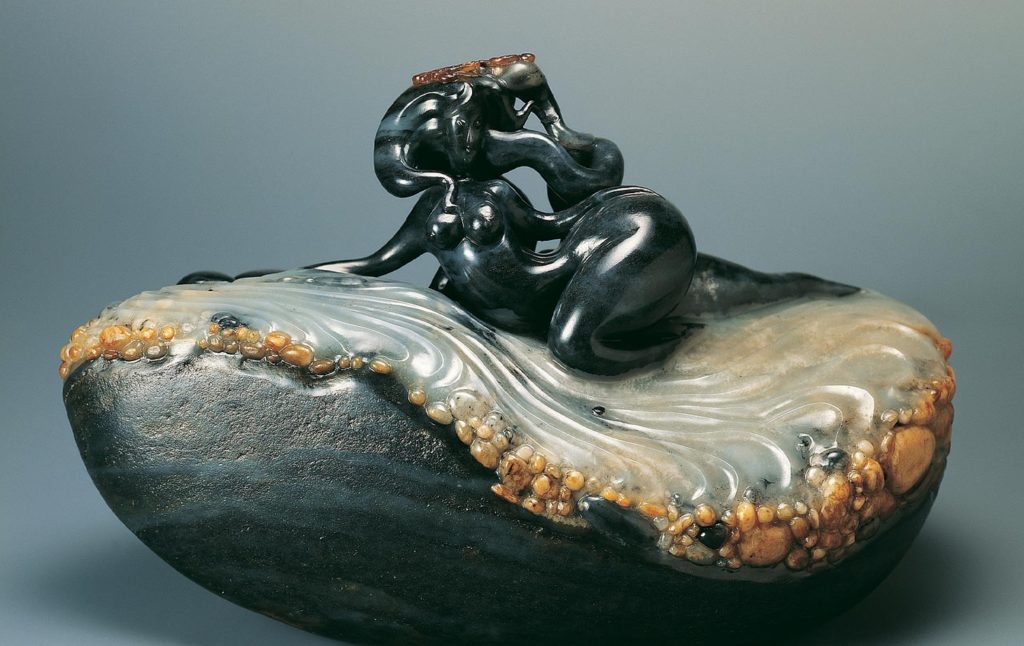

Once considered cast-offs, today carvers make creative use of these kinds of jade, turning yesterday’s waste into wonderful works of art.

Four types of Hetian jade.

Current Markets

Hetian, Xinjiang Province

Today Hetian is the most source trading market, mainly trading in rough jade and simple jade carvings. Recently, in order to upgrade facilities, the government banned many of the older dilapidated markets and moved them to the China Hetian Jade Trading Center, which is not far from the original market.

The whole center covers an area of more than 80,000 square meters and can meet the various trading needs for nephrite. Hotan holds the Hetian jade culture festival in late August every year. At that time, Hetian jade dealers, jade carving masters and literati from all over the country gather in a one-of-a-kind celebration of jade.

Since the late 1980s, merchants have gradually gathered in Urumqi, to form several major wholesale markets for jade. The larger centers include Hualing Jade Trading Market, Xinjiang Hetian Jade Trading Center, Xinjiang Jade City, etc. Currently, there are more than 2,000 listed jade shops in Urumqi. Urumqi is also a major processing centers of Hetian jade, and has created a distinctive local carving style.

Micro-structure of Hetian jade.

Shifosi City, Nanyang District, Henan Province

This small city in Henan Province is currently the largest trading place of Hetian jade in China. At present, Shifosi has nearly 15,000 jade carving processing enterprises of all kinds, more than 20,000 jade stalls, more than 300,000 employees, and an annual output of more than 20 million jade carving products. This accounts for about half of China’s Hetian jade carving industry. Every day, there are a large number of buses going back and forth to Shifosi and jade markets allover the country.

Almost all newly mined Hetian jade mine will pass through Shifosi before moving on to the rest of the country. Shifosi’s market is divided into raw materials, finished products and other secondary materials. Nanyang is also home to Dushan jade.

Jiangsu

Historically, Suzhou and Yangzhou of Jiangsu Province (near Shanghai) are the main processing places of Hotan jade. There used to be a saying that “Good craftsmen live in Beijing, but true artistry resides in Suzhou.”

Yangzhou is good at large-scale mountain carving, while Suzhou focuses on small accessories. Today, Suzhou has also become the creation and trade center of contemporary Chinese Hetian jade carving.

Three types of black jade.

The “Zigang Cup” held in Suzhou every year brings together not just the finest carvers of China, but the entire world, where they compete in a judged competition that is the Oscars of jade carving. The annual review is a bellwether of Chinese contemporary jade carving.

Treatments and Their Identification

River jade pebbles (jades from placer deposits) have the highest economic value. This is because of two factors. First, the weathering process where jade tumbles down a mountain and along the riverbeds is a winnowing process, stripping away impure and fractured areas. This is similar to alluvial diamonds and other gems which generally have much higher cutting yields than gems sourced directly from host deposits.

The second factor is the weathering process imparts stains to a certain percentage (about 30%) of the pebbles. Carvers love this material not just for its purity, but also the natural staining that can be taken advantage of in their artistic creations.

Because of the high prices paid for river jades, such stones have long been a target for imitation, and huge percentages of so-called “river jades” are actually clever deceptions.

The most common form is to take jade from the mountain quarries, saw it into smaller pieces and then process the stones in large industrial tumblers. Once the pieces have reached the desired “pebble” shape, they will then be artificially stained to complete the fraud.

While the unmasking of such forgeries is beyond the scope of this article, there are a few things to look for.

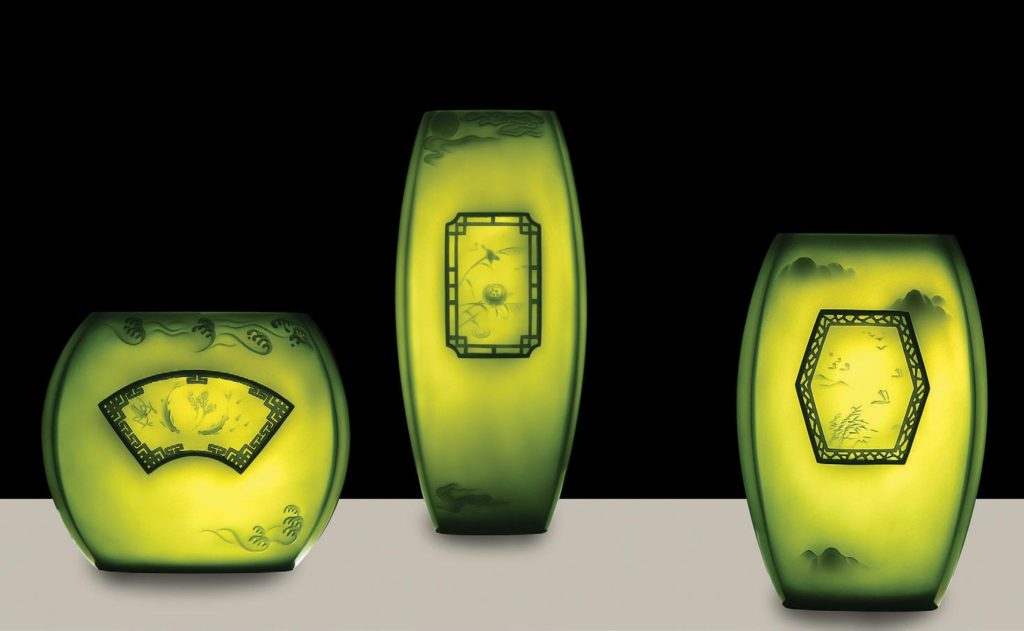

Utilizing white impurities in Hetian jade (nephrite) to create snow scenes. Carvings by Xia Shian.

Surface Morphology

For a long time, it has been considered that the absolute basis for the identification of the pebbles is the “sweat pores” of the sub material. The “sweat pores” refers to the phenomenon that the bumping pit on the surface of the natural jade which formed by the friction and collision between the jades and the riverbed in the process of water transportation.

However, with the use of emery spray guns and other methods, the market has realized artificial imitation of sweat pores, which are relatively uniform in depth and density and different from those natural materials.

Weathering Stains on the Skin

Thousands of years of weathering and surface exposure creates a rust-like rind (skin) on the surface of pebbles. The skin colors of natural pebbles are mainly composed of goethite, pyrolusite, limonite and other mostly Fe- and Mnbased minerals and mineral combinations. Therefore, weathering skin colors such as yellow, red, brown and black are seen, and multi-color mixing is common.

In contrast, most dyeing materials are organic dyes, and the common fake skin colors such as green and purple in the market are artificial dye residues. At the same time, single-color dyes are often used in artificial dyeing, and multi-color mixing is rarely seen. Because of the large differences in price between natural river jade and fake river jade, the technology of faking continues to move forward.

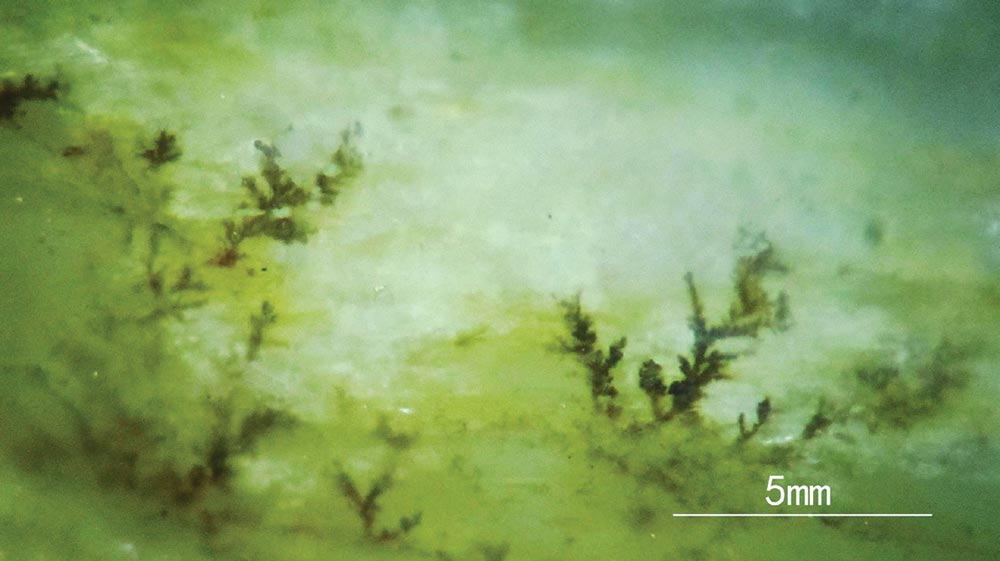

Today, artificial dyeing with iron salt, manganese salt and mixed inorganic salts is often seen. Identification of this kind of dye needs rich experience and expert identification skills. Natural weathering stains often form fractal structures, similar to the weedy patterns seen in agate, which cannot be found in dyed jade.

One of the best ways to unmask artificial skin stains is with a microscopic examination. Genuine stains tend to penetrate the surface and are difficult to remove, while artificial stains are more superficial and can be removed with even minor abrasion.

Imitations and Their Identification

Because of the increasing price of Hetian jade, sales of various imitations have also increased. The most common are quartzite, serpentine, and marble, along with glass, plastic and other artificial materials.

● Quartzite is commonly known as “Beijing white jade,” as it was first found in the suburbs of Beijing. Due to its porous

granular structure, it may be dyed a variety of colors. It can be separated by its lower specific gravity (SG) compared to nephrite (2.66 vs 2.95 for nephrite). Dyed specimens will show dye concentrations under magnification. Aventurine quartzite, a naturally green quartzite colored by chrome green fuchsite mica is sometimes called “Indian jade.”

● Serpentine, commonly known as “kangwa stone” (康瓦石). Nowadays, the term kangwa stone generally refers to all kinds of imitations of Hetian jade, which are only distinguished by color, such as white kangwa stone, green kangwa stone, yellow kangwa stone, etc., no matter what their composition is. Serpentine can be separated from nephrite by its lower SG (2.44 to 2.80), refractive index (1.56 to 1.57 vs 1.61 for nephrite) and hardness (2.5 to 6 vs. 6 to 6.5 for nephrite).

● Marble, commonly known as Afghan (or Pakistan) White Jade. Fine carbonate jade has a good oil luster, which is superficially confused with mutton-fat white nephrite, but there are big differences in hardness (3 to 4 vs. 6 to 6.5 for nephrite).

● Glass and other man-made materials, commonly known as “liaoqi (料器).” The name comes from Beijing Liulichang and other antique markets, originally referring to glass, and later extended to all the other synthetic materials. Glass imitations of mutton-fat nephrite are quite common. Magnification may reveal gas bubbles. The RI and SG of glass is also much lower than nephrite.

Due to technological innovations, identification of nephrite is more difficult. Not only are there clever treatments, but an ever-increasing number of both natural and artificial imitations. Today, the infrared spectrum has become one of the most effective nondestructive testing methods in the identification of Hetian jade and its imitations.

Surface observation characteristics of Hetian jade.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express immense gratitude to Richard and Billie Hughes for their help and advice in the preparation of this article. He also sends his thanks to all the craftsmen and craftswomen he has met over the years and for the wonderful jades they have shown him.

References and Further Reading

Chen Renxi (1581–1636 CE) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) compiled a complete history of China, the Qianqueju Series Books.

Lin, M. (1995) 西域文明—考古民族話言禾卩宗教亲斤论 [The Serindian Civilization: New Studies on Archaeology, Ethnology, Languages and Religions]. [In Chinese], Beijing, Dongfang Chubanshe.

Liu, X. (2001) Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies. Journal of World History, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 261–292.

Yu, Shen (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi 說文解字 [Interpretation of Words and Texts].

Dr. Zhou Zhengyu (征宇 周 – Adam) is Director of the Gemology Education Center of Shanghai’s Tongji University and is a world authority on Chinese nephrite. He has been engaged in teaching and scientific research of gemology since 2006. The author of three books and over 30 articles on all aspects of gems and gemology, he is also one of the editors-in-chief of China’s National Gemological Planning Textbooks for higher education.