The Maya Empire was an ancient culture that flourished in the first millennium AD in Mesoamerica, a term used to describe Mexico and Central America before the arrival of the conquistadores. Stretching geographically over what is today Guatemala, Belize, southern Mexico, and the western regions of Honduras and El Salvador, the Maya civilization reached its peak in the sixth century AD. Great city-states rose in the highlands and the jungle-covered lowlands. Metropolises including Tikal, Copan, and Palenque, and the late-period cities of Uxmal and Chitzén Itzá in the upper Yucatán Peninsula, had royal courts, temple pyramids, and enormous populations. The Mayans were passionate about architecture, astronomy, mathematics, the arts and… jade.

The Maya held jade in the highest regard. It was rare, valuable and represented eternity. Considering the gem to be the ultimate passport to the afterlife, they buried their kings adorned with jade masks and pectorals. They even placed a small piece of jade in the mouth of the dead, believing it to be the passport to heaven and that the jade’s spirit would be absorbed by the deceased and would ensure continued spiritual survival, thus elevating jade to “life-giving” status.

Among the colors of jade, green was the most precious. It represented the life-giving water of the Sacred Cenotes (natural wells); it symbolized crops and fertility; green was also the color of the extremely rare and valued feathers of the quetzal bird. In addition to burial masks, jade was carved into rings, ear flares, pendants, beads, and ceremonial objects. The gem was valued for its durability and ability to take a high polish.

A few years ago, my husband and I visited five major archaeological sites in Mexico—the pyramids at Teotihuacan, the Olmec heads at La Venta, and the pyramids and museums at Palenque, Uxmal and Chitzén Itzá. Following the Maya journey in Mexico, we returned to the area to visit the Museum of Archeology & Ethnography in Guatemala City, and the museums and pyramids in Tikal (Guatemala) and Copan (Honduras).

We spent time admiring the incredible collections of jade artifacts, carvings and beads housed in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, the Museum of Archeology & Ethnography in Guatemala City, and the Archeological Museum of Miraflores—the ancient Maya site of Kaminaljuyu, also in Guatemala City.

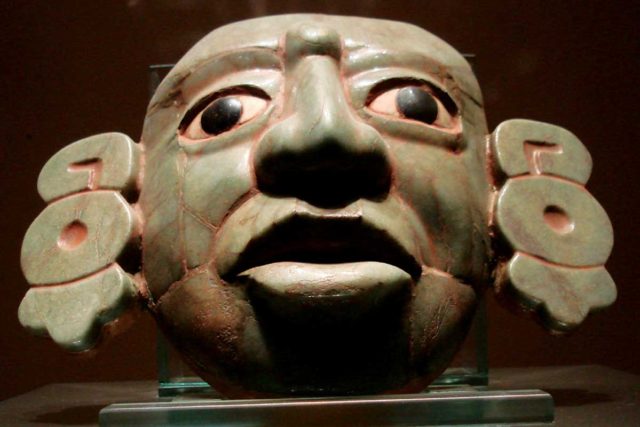

Among the many marvels was the impressive jade mask and pectoral of King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal I, or King Pakal the Great (Maya for War Shield, 683 AD) of Palenque, at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. King Pakal’s original tomb sarcophagus is in its original site inside the Temple of the Inscriptions in Palenque, Mexico. A copy of Pakal’s mask, created in 2001 by the Conservation Workshop of the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, is in the Palenque Archeological Museum. The original jade mask, pectoral and jewelry are on display in Mexico City, along with a replica of the King Pakal’s original tomb.

The Jade Minerals

Jade is a generic term that mainly describes two different silicate minerals—nephrite and jadeite.

Nephrite: A compact variety of the amphibole species of tremolite-actinolite, nephrite (Ca2(Mg, Fe)5Si8O22(OH)2,) is found in many places in the world, including China, British Columbia, Siberia, New Zealand and California. It occurs in colors ranging from pure white to green to black.

Jadeite: A sodium aluminum silicate and member of the pyroxene group, jadeite (NaAlSi2O6) is the jade mostly used by the Maya. The other major source of jadeite is Myanmar (Burma), where the famous translucent green imperial jade comes from. Very limited jadeite source also include California, Japan, Kazakistan, Korea and the Alps.

The Guatemalan jadeite often includes 10% diopside. Albite is part of albitic-jadeite’s composition, and the ferruginus variety dark chloromelanite (NaFeSi2O6+) is the intermediate variety between jadeite and acmite. (William Foshag, Mineralogical studies on Guatemala Jade, 1957, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections)

Omphasite jade (CaMgSi206), a pyroxene (sodium, calcium, magnesium and aluminum silicate) roughly half jadeite and half diopside, is the latest jade variety to be included in the international approved jade nomenclature in Hong Kong (Ogden, Gems & Jewellery Magazine, March 2013).

The English term jade is derived from the Spanish piedra de ijada (signifying flank, side, hence loin stone or colic stone) because it was supposed to cure kidney ailments. Natives in Brazil used jade amulets to cure diseases of the kidney. That belief spread in Europe and, by 1565, all jade had disappeared from Mexico. The term Lapis nephriticus was coined by Latin scholars in 16th-century Europe, a term which later became nephrite.

French professor A. Damour identified jadeite as a separate mineral from nephrite in 1864. His chemical analysis in 1881 proved that the Mexican stone was also jadeite. Thus, ironically and in an indirect manner after all these centuries, the Spaniards’ piedra de ijada came to be known with the modern mineralogical term jadeite.

Jade and Maya Culture

The Maya excelled in architecture, agriculture, and astronomy. They were the first people in the Americas to keep historical records. Besides their written glyphs on stone stelae, they wrote in Maya hieroglyphic script on folding books of Mesoamerican bark cloth, known as codices.

Although the Pre-Classic period dates as far back as 1800 BC, the Classic Period (the pinnacle of the Maya civilization) lasted from 250 to 900 AD. After that date, the downfall of the Classic Maya began, and most cities were abandoned. The cities in the northern Yucatán Peninsula lasted longer as many of the Maya people retreated there, until it all came to a violent end with the invasion of the Spaniards in 1517.

The many reasons for the collapse of the Maya civilization are still debated among archaeologists, who consider population density, increased warfare, revolts, long-lasting droughts and agricultural collapse as the main causes (Michael D. Coe, Breaking the Maya Code, Thames & Hudson, 2012). Yet, the permanent harm to the environment caused by clear-cutting forests due to urban sprawl and the burning of trees for the production of quick lime is gaining scientific support, and seems the most rational reason for the decline. Local limestone was pulverized and thermally decomposed, and when combined with water, it created the valuable lime plaster, which was used as a base coating

before repainting the floors and walls of their pyramids and buildings, a restoration that was repeated as often as every three years.

With the decline in Maya culture, the sources for Mesoamerican jade were lost, and remained lost for more than five centuries. This was primarily due to the general lack of interest in jade by the Spanish conquistadores, who were mainly interested in gold and emeralds.

However, reports in diaries kept by early Spanish explorers document the special status of a gemstone unknown to them, one that would later to be called jade.

In the account by Captain Bernal Diaz del Castillo of his service to Hernan Cortez entitled The True History of the Conquest of Mexico (1568/1632), he attests to the value placed on jade by the Mesoamerican Indians: “Montezuma (the 9th ruler of Tenochtitlan 1502-1520) also sent four jewels called calchihuis, resembling emeralds, most highly valued by the Mexicans (Aztecs)…these rich jewels… were intended for our emperor…each stone is worth two loads of gold.”

The term calchihuis or chalchihuitl is apparently a Spanish aberration of the Nahuatl word xal-xihuitl from Xalli (jewel or sand) + xihuitl (herb or herb-colored). (Foshag 1957). The Maya word for precious stone was tun and yaaxaltun for green stone (piedra verde).

In the early days of the Spanish conquest, the Maya people kept the location of their jade mines a secret, to protect them from the invaders. Over time the location of the ancient mines and quarries became forgotten and lost.

Rediscovering Mayan Jade

The amazing story of the gem’s rediscovery extends over almost the entire 20th century. Although many carved jades have been found in archaeological sites in Central America since the early 1900s, no rough jade specimens were found in situ until much later.

In 1894, Edward Herbert Thompson (1857-1935)—an American-born archaeologist and diplomat— purchased the Hacienda Chitzen, which included the ruins of Chitzen Itza, and explored the ancient city for 30 years. He dredged the Cenote of Sacrifice between 1904 and 1910 and retrieved gold, copper and many jades. He shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard.

Today, the location of many of the ancient mines is known and a magnificent variety of jadeite colors is now mined in Guatemala. Jadeite in every shade of green is collected there, as well as white, creamy yellow and blue as well as a rare lavender.

Jade boulders of different colors can be found side-by-side in the field, even boulders with various colors. It is unknown if the Maya found the lavender-colored jade, or if that color simply did not fit their symbolism.

The rediscovery of Mayan jade involves many American scientists enamored with the gem. Among these early jade explorers was Zelia Nutall (1857-1933), an American archeologist and anthropologist from San Francisco. Known for her Mexican archeology research, she published for the Peabody Museum. Her 1901 article Chalchihuitl in Ancient Mexico describes Aztec tribute lists, which indicate jade native sources in southern Mexico.

The Scottish William Niven (1850-1937), a mineralogist and archeologist who came to the USA in 1879 found jade nodules in 1910 in the Del Oro and De las Balsas rivers in Guerrero, Mexico.

Robert Leslie, an American chemist and rockhound working on an agricultural project in the Motagua River Valley of Guatemala, discovered jadeite in 1952 just east of the town of Manzanal. Fellow American William Foshag, a geologist and curator of the Department of Mineral Studies at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, spent several years in Mexico and Guatemala in the 1940s studying the ancient jades and geology of the area. He wrote about Leslie’s 1952 discovery in his article Jadeite from Manzanal, Guatemala (Journal of American Antiquity, July 1955).

In Foshag’s 1957 Mineralogical studies on Guatemala Jade, published a year after his death (Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections), his research using X-ray diffraction patterns and refractive indices categorizes the Guatemalan jade as jadeite, and found it to be similar to Burmese jade. (Never Jaded: A Look at Field Notes, article by Courtney Esposito, SIA/IHD, Smithsonian Institution Archives).

An American couple, Tom and Joyce Barbour, also searched for jade in Guatemala and described their adventure, but unsuccessful search for the elusive gem, in the April 1964 issue of Lapidary Journal.

More recently, credit goes to an American expatriate couple, Jay and Mary Lou Ridinger, who used the earlier research of their predecessors to find Mayan jade. For months, they searched and finally found their first outcrop of green jade on a tributary of the Motagua River in 1974.

They sent samples to GIA and other labs, and all confirmed their finds as jade. In 1998, the couple found lavender jade and, in 2004, found small amounts of translucent “emerald” green jade, which they call Maya Imperial Jade.

The Rio Motagua flows along the earthquake fault line between the North American and the Caribbean plates. Jade is formed deep in Earth’s crust and is pushed up under very high pressure and low temperature conditions (Mary Lou Ridinger, DVD The Mysteries of Jade, Discovery Channel).

The Ridingers have found jadeite in several locations in the Motagua River Valley by surface collecting only. There is no underground mining. They often heat the jade boulder and then throw water onto it to create cracks. Gasoline-powered jackhammers are used to remove jade lenses from the boulders. Then the boulders are driven to the Ridingers’ factory in Antigua (Jadeite of Guatemala: A contemporary View, David Hargett, Gems & Gemology, Summer 1990).

Describing the jadeite that they discovered, Mary Lou explains, “If you have inclusions of copper or chrome, you have green jade. If you have manganese and ferrous iron, you have black jade,” adding that jadeite’s physical appearance is granular, with a greasy luster. It has a hardness of about 7 on the Mohs scale, a refractive index of 1.65-1.67 and specific gravity of 3.20-3.34.

They also discovered a scarce variety of deep black jade with perfect cubic pyrite inclusions and flecks of precious metals—silver, nickel, cadmium, platinum, and gold. It was given the very appropriate trade name Galactic Gold. After I donated a slab to the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (Gem-A), a Raman spectrum test run by the Canadian Institute of Gemmology proved the slab to be omphacite, the latest jade variety to be included in the international approved jade nomenclature. (Ogden, Gems & Jewellery Magazine, March 2013)

The Ridingers also found and identified centuries-old Mayan workshop sites. Excavation at these sites produced tools and small bits of pottery indicating where outdoor carving had once taken place (Mesoamerican Jade, Anna M. Miller, Lapidary Journal, February 2001). Mary Lou told me when we met at her shop in Antigua that it was the ancient lapidary shop sites that led them eventually to the rediscovery of the ancient jade mines.

The hunt for jade is grueling, complicated, and dangerous. Besides the dangers to gringos exploring the countryside during the civil war at that time, the sweltering heat and poisonous scorpions and snakes can be real hazards. Compounding the problems, it is also difficult to identify the jade boulders in the field since their surface is covered by a rind similar to the bark of a tree. What helps distinguish jade from the various rocks in the field is by pounding the rocks with a 10-lb sledgehammer. “Jade is so hard and dense,” says Mary Lou, “that the hammer will bounce off the jade boulder and will make a unique ringing sound.”

The Ridingers also tested jade in the field by submerging specimens in a methylene iodide test fluid, blended to a specific gravity of 3.0. Jadeite will sink, while other green stones including serpentine, nephrite and chrysoprase will float.

Just as the Ridingers tested jade in the field for specific gravity, Fred Ward had several jade carvings tested by Smithsonian archeological scientist Ron Bishop, who submerged the specimens in the same methylene iodide test fluid. Ward also took geologist Brian Curtiss to Guatemala to test the famous funerary mosaic mask from Tikal with a portable PIDAS spectrometer from the Jet Propulsion Lab, in order to determine which parts were jade and which were not. The test confirmed Mary Lou’s earlier visual identification that only the mask’s ear flares are pure jadeite, while the rest of the green pieces are jadeite-diopside mix.

Mayan Lapidary Work

How were the Maya able to carve their jade? Mary Lou Ridinger explains, “They carved jade with a wooden blade made from the local hardwood lignum vitae with an adhesive that could carry crushed garnet or jade as the abrasive.” Garnets are found in alluvial deposits in the same area near the Motagua River. At the Tikal Archeological Museum, I admired the length of carved imperial green jadeite beads— many between two to four inches long. It takes a while to drill such holes even today using diamond tools. The ancient lapidaries used a wooden bow drill with a bamboo shaft and abrasive, and/or a stone tip. I have total respect for my fellow ancient Maya lapidaries, their ability and time invested in their work.

In the Mexico Gallery of the British Museum in London, the Olmec, Maya, Aztec, and Mixtec cultures are represented. Besides the amazing Aztec turquoise mosaics is a collection of Maya carved jades. Among them is a fabulous imperial green jade plaque, which shows a Maya lord in full ceremonial regalia seated on a throne, with a smaller figure at its feet. The lord wears earplugs, pectoral, armlets, wristlets, belt, and headdress. The plaque dates from the Late Classic period ca. 600-800 AD, and measures 14x14cm. It was found in Teotihuacan, possibly from the Nebaj area in the western Guatemalan highlands.

We also had a wonderful opportunity to see and touch a special collection of carved jades at the Cultural Research Center of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), a part of the Smithsonian Institution. This collection is open to researchers, but a two-month advanced appointment is required, along with a precise list of items to be researched.

Museum specialist Victoria Quiguango gave us a brief tour of the center, which houses thousands of items, including a large number stored in secure vaults. Among the collections are a small number of beautiful Maya jade carvings. The items on my written request list came out of the vault on a rolling cart. Wearing protective gloves, I examined several Mayan carved jades under the specialist’s supervision. Some of the elaborately carved pendants were three to four inches long with drilled holes. The polish of the carved jades was extraordinary, even still today.

Modern Jade Carving

Our jade journey included two visits to the Ridingers’ Jade Maya™ Gallery in Antigua, Guatemala, which is also a factory for carving jade and an archeology museum. Jay Ridinger set up the lapidary shop with equipment from the USA. Robert Terzuola, another jade-loving American living in Guatemala became a master carver and was the shop’s foreman for several years, training Guatemalan apprentices (Green Gold, Donald M. Best, Lapidary Journal, October 1983). His name is given to an ancient workshop site that he discovered, dating to 750 AD, now known as the Terzuola Site, east of Guatemala City. Jade chips were found at the site, including two cores from holes made by a hollow drill. (Jade Workers in the Motagua Valley, Lawrence H. Feldman & Robert Terzuola, University of Missouri, 1975).

During each visit to the Jade Maya™ Gallery, we were welcomed by Mary Lou Ridinger and energetic shop manager, Raquel Pérez, who allowed us to visit every room and workshop. The tour began with guide Raphael Martinez at the at the slab room, where the rough material from their seven quarries is cut by large saws. The slabs are sorted, graded and numbered 1 to 14, corresponding to the final finished cabochon grades. In the impressive inventory of sorted jade slabs of all colors and grades are rare Maya Imperial Jade and Mayan Foliage—the popular green and white mottled variety. All their jade material is natural and untreated.

In the workrooms, skilled workmen carve beautiful replicas of ancient artworks, with motifs that reflect their artistic traditions. Many of these Guatemaltecos are of Mayan decent.

In the gift shop, various replicas of King Pakal’s mask and other ancient Mayan mosaic masks and sculptures are displayed, as well as original designs by contemporary jade sculptors. Jade jewelry set with other gemstones and pearls, is also for sale, including some by Andrea Novella (the Ridingers’ granddaughter).

Inspired by these ancient Maya and contemporary jade carvings, I began creating my own Maya Jade Collection. Although the green jades are best known and most desired, my favorite Guatemalan jade color is lavender. It is easy to carve, following standard lapidary steps. Carving the black Galactic Gold jade pieces was as dirty as with any other material that has pyrite inclusions. The black residue color— both from the black jade and the pyrites—stains everything.

Each of my jade artwork “tells a story,” a story that shares the beauty, history and lasting friendships of my Guatemalan jade journey.

Unless otherwise specified, all photos are by the author